Now that personal electronic device use is permitted gate-to-gate on the bulk of flights in the USA (and most of the rest should be on board soon) the question becomes what about gate-to-gate connectivity? When will travelers be able to use WiFi throughout their trip rather than only above 10,000 feet? Alas, the answer isn’t nearly as easy as it should be.

Airlines using Gogo‘s Air-to-Ground (ATG) service won’t have access to such functionality anytime soon. The system is built to work when the planes are at altitude and changing that is unlikely both for cost and technical reasons. So strike Virgin America, Delta, US Airways and American Airlines from the list of possible options. For United Airlines, JetBlue and Southwest it is technically possible – the satellite systems they use should work the same on the ground as they do at elevation – but that doesn’t mean it will be enabled immediately. There are some configuration changes which will be necessary in the kit on those planes and that sort of thing takes time to test and deploy.

But that may not even be the most significant factor driving (or delaying) the activation of gate-to-gate internet service. As is often the case, money may have something to do with it. Average stage length across the three carriers ranges from 950 miles (Southwest) up to nearly 1,900 miles (United mainline). Some back-of-the napkin math says that the flight time on average ranges from 1:50 to 3:40 with approximately 30 minutes of that time below 10,000 feet; that suggests the average WiFi available time on a flight is 1:20-3:10. Switching to a gate-to-gate access system would mean adding that 30 minutes of usage back in to the calculations. Plus there is another ~20-30 minutes on average for taxi time at both ends of the flight. Adding 60 minutes of usage on is a 75% increase for at the shorter end of the average and 30% more for the higher end (and, of course, those numbers are averages per carrier so the math is all a bit fuzzy).

Airlines are buying the bandwidth by the megabyte and selling it at a flat-rate to users. The increased potential usage time means the costs to the airlines are likely to similarly increase should the policy change. Mary Kirby from Runway Girl has some numbers suggesting that a megabyte of data delivered to a user on a plane costs somewhere in the 10-20 cents range for Ku-band (Southwest and United) and in the 2-5 cents range for Ka-band (JetBlue and United 737s). So a $10 pass for a flight should cover 50-100 megabytes of Ku service, not accounting for the up-front cost of installing the hardware on the plane. Extend the usage time by 30% on that same flight and just how much does the actual bandwidth consumed – and the cost to the airlines – increase? Probably not linearly but it is definitely more than zero. My best guess is that we’re looking at a couple dollars extra per passenger in costs to the airlines (or connectivity providers if the airlines aren’t involved in the transactions) for the bandwidth being provided. Multiply that out by a few hundred users a day and it isn’t too bad. By a few thousand users a day and it starts to become real money pretty quickly.

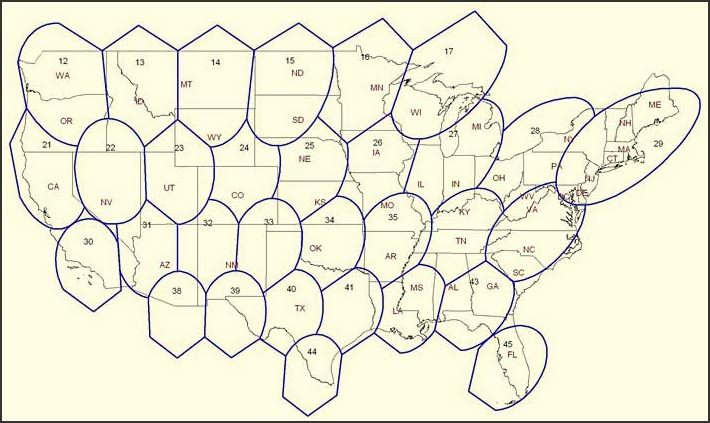

There is also the factor of adding in more users in general. A customer today who decides to not buy the service because the flight is too short may choose to purchase the service on a future flight once the extra hour of access is included, making the expense justifiable overall. That means more competition for bandwidth on the individual flights and more competition for bandwidth from the satellites in general. The current overall capacity should be OK in the aggregate but there the flights are not evenly distributed across the country. The coasts see a much higher density of traffic, much of it shorter trips where usage is lower today. With the longer access times those flights are likely to see take rates increase. For the Ka services this may be less of an issue; the ViaSat-1 satellite has specifically focused its coverage on the coasts, boosting the capacity available over the bandwidth provided by the WildBlue satellite it shares duty with. For Ku-band providers the spot options aren’t really available today, though Panasonic expects to have service operational in the 2015-2016 timeframe. Until then the saturation risk remains somewhat higher.

At the end of the day it is almost a certainty that the ability to use WiFi from gate to gate will happen on the airlines where the service is supported. But that progress comes with a very real cost, something that either the customers or the carriers will have to absorb. And given the way airlines latched on to ancillary fees it seems unlikely that the customer is going to get away for free on this one either.

Never miss another post: Sign up for email alerts and get only the content you want direct to your inbox.

Sure someone has to pay for it…but like DirectTV, the salty are sugary snacks sold on the plane, or the $9 Bacardi and coke in the club….it won’t be me buying it.

Panasonic Avionics for the Ku-band win (2014-2016)

Larger devices still need to be stowed during taxi, takeoff, and approach. And at present the FA announcements say small devices need to be in airplane/non-transmit mode. The bandwidth impact may not be all that significant if larger devices have to be stowed until the 10,000 feet double chime and vv.

Still believe this is a bad idea for safety reasons. As I understand it only laptops and large PED’s need to be stowed during critical phases of take off and landing. If there is an accident I’m really not sure I want a 7″ iPad (nice sharp edges) flying around the cabin. If you get hit in the head with one of these devices it will cause serious injury. These devices are not tested for head strike like the embedded IFE screens in your seat.

There is a reason most aircraft satellite systems are not used on ground:

1.Line of site required – terminal stand position and height of surrounding structure may not allow for this.

2. Plate Temp – For internet services you need transmit capability which in turn will cause temperature rises on the Antenna plates. Most are designed to work above 10k Ft to allow for the necessary cooling. They are not meant for extended use on ground in hot climate areas. Phased Array antennas may get around this issue but we are still years away from putting these on commercial aircraft.